So I’ve learned a thing or two about audio and video production in the last couple of years.

I’m nowhere near an expert, I don’t know how to do those fancy SWOOSH transitions between cuts the kids seem to love, but I think my stuff is at least watchable now.

AND THAT’S WHY THIS VIDEO IS SPONSORED BY SKILLSH-

I guess that’s true of my early videos too, since my original video on the enarees is still my most viewed video other than the intro one, but I think that’s because the enaree priestesshood is one of the most commonly discussed bits of trans ancient history I see being passed around online.

But even still, as I see the topic discussed, I’m sometimes reluctant to share the original video I made. The ideas are mostly intact – mostly, I did make some mistakes – but what was I doing with the lighting there?

It’s not supposed to wash out like that. And the audio, yeesh! Girl have you heard of noise reduction or pop filters?

No. The answer is literally no, I hadn’t.

So it’s time for a fresh take.

I got people comparing me to someone named Contrapoints in that video a bunch too. Well, not a bunch, but more than once at least. So I looked her up and I guess she’s like some big popular YouTuber or something?

And I guess we’ve got some stuff in common, but she makes a lot more money than I do and has way more subscribers. So really, we’re not the same thing.

But look, people are also in my comments all the time telling me they think this channel should have more subscribers. Well, not all the time, because I don’t have a lot of subscribers, but more than twice at least.

If I had more subscribers, maybe I’d have more people telling me I need more subscribers.

Anyway, I agree, this channel should have more subscribers! I think the subject matter is pretty neato, and I like that I can help people to know more about it.

But this Contrapoints person, whoever she is, she’s got more subscribers than I do. So maybe I should do what she does.

So let’s see. She’s a leftist trans lesbian in her 30s with a vaguely witchy vibe who sporadically releases absurdly long video essays on niche topics she’s currently obsessing over, plays an instrument, and has a spotty relationship history.

Sounds good so far.

But I don’t know, I guess the vibe could be witchier. Maybe I need more spooky stuff?

(grab Button, put straw broom in the background, and put up some stupid Halloween decorations)

Okay, we’re on pace now. I can feel the algorithm panting, licking my cheek like an excited puppy. I hope it doesn’t wet the floor.

I guess she wears a lot of silly costumes too. So all I have to do is put on a silly costume and the new subscribers will just start pouring in, right?

(print out like, comment, and subscribe button, put them on springs, stick them to those flamingo glasses I have along with some other junk, wear it in the next part)

Like! Comment! Subscribe! Patreon!

Surely we’re a successful channel now!

(fake phone call, answer it)

Oh, what’s that? You’re saying I have to have actual substance as well?

(sigh, take off dumb glasses)

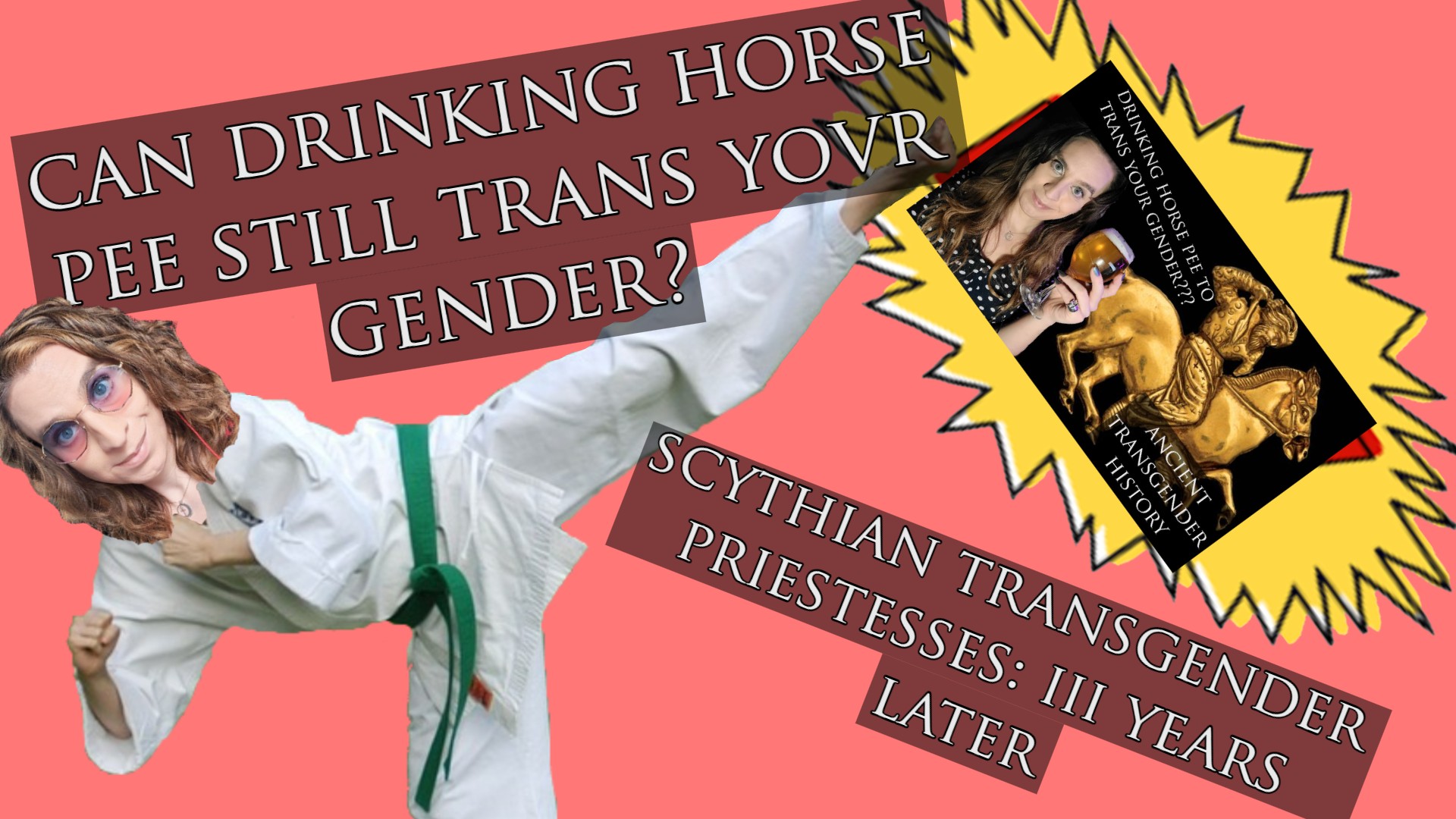

This is going to be the first in a new transgender history series I’m going to do on the enarees. We’re going to cover what we’ve already looked at in the previous video, and expand on some of the previous points. No CGI Jabba though – this is some actual substance.

Think of this as sort of like the deluxe edition, the third anniversary edition, the rerelease of old material you get when someone has run out of ideas and wants to milk their greatest hits for all they’re worth.

Well, hopefully not the last part, I *do* have other ideas.

Also – this video is sponsored! By me!

That’s right, my debut novel is either out already, or will be soon, depending on when this is released.

It’s a story about identity, and how we find ways to create our identities and find meaning in the world, and what happens when that’s taken away from us, and I explore that through automation. The Bottom Line focuses on a crew of construction workers in near-future Toronto whose jobs are being replaced by robots. They’re still taken care of once they’re replaced, a sort of UBI thing, so the conversation isn’t “how do I pay my bills,” it’s “what do I do with my life now?” And if you’ve got hobbies, interests, creative pursuits, community, etc, that might be awesome. But if you’re the type who draws a lot of your identity from your work, such a future might be horrible.

I started writing this thing like ten years ago, and it’s pretty surreal to have it be an actual physical thing that’s in the world now, and not just a file sitting on my hard drive.

Anyway, links in the description below to grab your copy, in ebook or physical format.

But if you’re a Patreon backer, you’ll get a special ebook edition of The Bottom Line. Link in the description as well.

What does The Bottom Line have to do with trans history? Nothing at all. Not even a little bit. But hey, I’m multifaceted, I guess! Maybe you are too.

Good lord how much longer is this preamble going to be???

(title screen)

They say history is written by the victors, but in ancient times that wasn’t always true. In fact, history was written by the people who bothered to write it.

When you think of the ancient Mediterranean, a few names probably come to your head – the Romans, the Greeks, the Egyptians. But the only reason why we know so much about them, and so little about all the others, is because they’re the ones who wrote the most stuff.

Take a look at this map, for example. See all that green? That’s the Achaemenid Persian Empire at its greatest extent, around 500 BCE. And that little tiny bit of red? That’s Athens at the same time. Clearly one is much more important than the other.

Around this time, Athens itself had an estimated population of around 100,000, and another 200,000 or so living in the countryside around it (Villing). That’s a pretty big city for the time. But the Persian Empire had somewhere between 17 and 35 million people (Morris & Scheidel, 77). There’s just no comparison, and yet, historians won’t shut up about Athens.

Why?

Because the Athenians wouldn’t shut up about themselves.

Meanwhile, the Persians didn’t write a lot.

But they did write.

There are plenty of other cultures, though, that never bothered to write anything down at all. In these cases, everything we know about them comes from either archaeological evidence, or from outsiders – usually Greeks or Romans – who wrote about them.

One of those cultures is the Scythians.

Maybe this is a culture that’s completely new to you, or maybe you recognize them as a playable faction from Civilization VI. But either way, we’re going to take a closer look at the Scythians. We’ll explore the part of the world they were from, and some details we know about daily life as a Scythian from the archaeological record. Then, we’ll take a look at the pretty conclusive and rad as hell evidence of a sect of trans feminine priestesses within Scythian society, called the enarees.

Finally, we’ll address the idea that the enarees figured out a natural form of trans feminine HRT 2500 years ago, and how true that might have been.

When I first learned about the enarees, it was one of the coolest things I’d ever heard, and yet it was a struggle to find any information about them. I had to do some pretty deep dives into the ancient sources, and pull out some little tidbits here and there from modern historians writing about the Scythians. But as the picture became clearer and clearer to me, I became more and more excited about what I was learning.

It was the enarees, in fact, that made me want to put this channel together in the first place. People oughtta know this stuff, y’know?

Without further ado…

Who Were The Scythians?

Let’s start with a brief overview of who the Scythians were. After all, they’re not one of the more well known ancient cultures, they’re pretty obscure, you probably haven’t heard of them. But unlike the Phrygians, who we talked about in the video on the gallae where I originally made that joke, the Scythians weren’t really influential on much. So unlike a band like Liliput, who’s relatively unknown but who influenced Kurt Cobain and therefore had an influence that spread pretty far, the Scythians were more like, I don’t know, Guitar Vader.

Do y’all know Guitar Vader? Japanese band, they had a couple tunes on the Dreamcast game Jet Set Radio. Great game, don’t play it, it hasn’t aged well. But they’ve got two songs on there – Super Brothers and Magical Girl, and both of them are great, which got me to dig into the rest of their excellent discography. They’ve got five full lengths, a remix album, and some singles floating around, and every song they put out is a total banger. But other than nerds like me, nobody seems to know or care about them. Start with the album From Dusk, it’s a fun mix of indie rock, pop, and even some electronic elements, really innovative stuff, I’ve never heard anything like it.

So the Scythians are like Guitar Vader.

And like Guitar Vader, the Scythians were from Asia.

They lived mostly in a region known as the Great Steppe, a vast swath of grassland stretching from modern day Bulgaria to the north Pacific coast of China. It shaped Scythian culture in ways too numerable to mention, so to understand them, we need to understand the region.

If you’re familiar with Genghis Khan’s Mongol Empire, the Great Steppe is where they first started, and it made up a large chunk of the empire. That’s like 1500 years in the future from when the Scythians lived though, so if you’re not familiar with the Mongol Empire, don’t worry about it.

The Great Steppe is really something, so let’s go take a look.

(stock footage of a plane taking off in fast forward, then some clouds looking out from the window of the plane, then stock footage of the plane landing but it’s just the plane taking off in reverse. Then full length shoot of myself standing upright in the Steppe)

Here we are on the Great Steppe.

Yes, I’m actually here. Take a look, here’s me, there’s the Great Steppe behind me. What the heck is a green screen? I don’t know what you’re talking about.

The Great Steppe is considered some of the easiest territory for horseback riding in the world, and the Scythians took advantage of that. As a nomadic culture, the horse was always very important to them, and features in a lot of their art.

It’s flat, and warm enough for things to grow, but too dry to sustain many trees. Instead, you get a whole lot of grass, and some small shrubs. That’s a big reason why there’s not a lot of rice in the cuisine of Mongolia, for example, compared to other south and east Asian countries. It takes up to 5000 litres of water to produce a single kilogram of rice (WWF, 6), and there’s just not that much water available in the area to make that happen (World Bank).

There are some plant based foods available, but not a lot, so people of the Steppe tend to rely on livestock. But since there’s so little rainfall, it’s easy for your livestock to eat all the grass in the area. That means you have to be constantly looking for new ways to keep your animals, and therefore yourself, fed (Cunliffe, 62-65).

Look, you can ride for an entire day and not see anything other than grass and the horizon. That, plus the factors above, meant the Scythians tended to move around a lot. So where did they go?

North would take you into the harsh winters of Siberia, so you don’t want to go too far in that direction. So you’ve got three real options – move south and southeast, into China. Move southwest, into India. Or move west, toward Europe. And the Scythians did all three, depending on conditions at the time. That’s why they built the Great Wall of China where they did – it’s essentially a border marking the edge of the steppe, and helped keep the Scythians and other steppe nomadic groups out (Shelach-Lavi Et. Al, abstract). But the Great Steppe spreads across Asia east-west, so moving west was the only way they could stay in territory familiar to them (Cunliffe, 64).

Now, when we think of ethnic groups of people, we might think of them in the sense of modern nation-states. Italian people, for example, mostly live within the well-defined border of the Italian state. Some of them might have moved to Germany, or Switzerland, or Canada, but most of them are, of course, in Italy. People in one part of Italy know more or less what’s going on in other parts of Italy, and there’s a general sense of Italian-ness, even though it might be stronger in some parts of the country than others.

But most ancient cultures didn’t work this way.

As the Scythians moved westward, they eventually started settling around the Black Sea. This is the Pontic Steppe, and it’s the same area where Mithradates and Hypsikrates would consolidate their power after their defeat during the Third Mithradatic War. We talked about that in the video on Hypsikrates, check it out.

We know the most about the Black Sea Scythians, because they lived the closest to the Greeks and Romans, who visited them and wrote about them. And we can tell through archaeology there were some cultural similarities with these Scythians and the ones who lived further east, but it’s questionable whether they knew each other even existed. That, plus the fact that they didn’t write anything down, means there’s a whole lot about Scythian life we don’t know much about.

We do our best based on the information available, but the reality is we’ll never have the answers to most of our questions. But that doesn’t mean we’re completely hopeless.

Of course, this is a transgender history video, so we’re going to be looking at the more trans-y elements of Scythian life and culture.

We know they were called the enarees but what do we know about them?

Before we answer that, let’s take a moment to understand how we know about them.

Ancient Primary Sources

So for our purposes today we have three significant ancient sources when it comes to assembling a picture of the enarees – Herodotus and Pseudo-Hippocrates, both Greeks, and Ovid, a Roman. Other sources mention them briefly as well, including Aristotle (Eth. Nic. VII.VII), but they’re less important here.

Let’s take a moment to understand each of them.

Herodotus

(Mega Man 2 boss intro thing, sped up and pitchshifted, with Herodotus’ head stuck on the fighty guy)

Herodotus was born in the Greek city of Halikarnassos in about 484 BCE, which at the time was part of the Persian Empire, and today is in Turkey. His father was Lyxes, and his mother was named either Rhoio or Dryo – we’re not sure. As a young adult, he was exiled from Halikarnassos by its ruler Lygdamis – no, not Ligma, get your mind out of the gutter – Lygdamis was the grandson of Queen Artemisia, who we talked about in the video on Hypsikrates as well – all this stuff is connected.

Anyway, once he was exiled, he apparently traveled a lot. He even returned to Halikarnassos once Lygdamis was deposed, and sent back to where he came from – Lygdamis ruled Halikarnassos, but he was actually Sugondese (I’m so sorry).

But Herodotus didn’t stay in Halikarnassos. At some point he probably lived in Athens, and was probably friends with the poet Sophocles, but he eventually settled in Thuria, in modern day Calbria, Italy (Rawlinson, V-VI). And that’s about all we know about his life.

His travels, research, and notes were all compiled into a collection called Histories, which is considered the first piece of proper historical research – sort of the Black Sabbath of history writers. For this, Cicero called him “the father of history” (Cic. Leg. 1.4).

He seems to have traveled across Persia, Egypt, mainland Greece, Babylon, and, of course, Scythia.

Pseudo-Hippocrates

Pseudo-Hippocrates, on the other hand, we know almost nothing about.

(who’s that Pokemon, pitchshifted & sped up, but the question thing never disappears)

We have a collection of about 60 different writings on medicine from the ancient world called the Hippocratic Corpus. It was attributed to Hippocrates, whom you might recognize as the Hippocratic Oath guy. But here’s the fun part. There’s no evidence Hippocrates himself wrote any of it, and it’s very clearly written by more than one person. We can tell based on both stylistic and philosophical differences (North). There’s a long, ongoing debate on who wrote what, and how many writers there were – it’s a mess.

But we don’t really know what to say about the author, so we just say the whole thing was written by Pseudo-Hippocrates because that seems like as good a name as any.

What, you think you got a better idea?

There’s a lot of interesting stuff in the Hippocratic Corpus, but we’re only looking at one piece today – “On Airs, Waters, And Places.” The author of this one talks quite a bit about the Scythians in a way that makes it seem like they’d been there. We think it was written around the same time Herodotus put his work together.

Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso was his full name, and he lived during the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus , the end of the 1st century BCE and the beginning of the 1st century CE, so like more than 400 years later than Hippocrates. We know A LOT about his life, and I could go on for awhile, but I’ll condense it as much as I can.

Ovid was born on March 20, 43 BCE, in a town called Sulmo, about 150 km east of Rome. Today it’s called Sulmona. His brother Lucius was born exactly one year earlier, which would have been just five days after Julius Caesar was assassinated. Theirs was an upper class family, the Gens Ovidia, and the two boys were granted the rank of equites — equestrian, an aristocratic title – at a young age. It was assumed they would make their way through the cursus honorum, climbing the ladder of Roman politics. At around 12 years old, dad sent them to Rome to continue their education. There, Ovid caught the eye of Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus, a wealthy patron of poets, and devoted himself to poetry. Dad wasn’t happy about this – he reminded Ovid that Homer died poor. If you’ve ever taken a creative pursuit seriously as a career path, that might sound familiar.

By the way, did I mention I wrote a novel? Link in the description!

Meanwhile, Lucius pursued oratory and law. Ovid married his first wife when he was sixteen, but the marriage didn’t last long.

He gave his first public poetry reading around age 18, and shortly after he left Rome to travel across Greece, Sicily, and Asia Minor for two years – you know that whole gap year thing, where wealthy kids go backpacking across Europe to “find themselves” or whatever? That was a thing for the Romans too. While he was gone, his brother Lucius died.

Returning to Rome, he held some legal and administrative positions, during which time he wrote enough poems to publish the first edition of the Amores, which holds one of the poems we’re most interested in today. After that, in 16 BCE, he finally rejected a career in government, and became a full time poet.

Another marriage, another divorce, a third marriage, and a bunch of poems later, Ovid was about 45 years old. His work was celebrated, and he was well known in the important social circles in Rome. But at some point, he did something to upset the emperor Augustus so badly that he was kicked out of the empire altogether. What did he do? We don’t know, I wish we did. It’s a pretty serious punishment. Ovid says it was “carmen et error,” a poem and an indiscretion (Ov. Tr. 2.207) but that’s all we have. But whatever it is he did, Augustus ordered him to leave not just Rome the city, but Rome the state overall.

And this is the Roman state at the time.

Most of the known world that wasn’t under Roman rule was undeveloped wilderness with some scattered barbarian tribes. And that’s going to be tough enough for a big strong warrior, which Ovid was not. Where’s a poet going to go?

He decided on the city of Tomis, on the coast of the Black Sea. At the time it was the edge of civilization, but today it’s the city of Constanta in Romania.

And he was miserable there. Absolutely miserable.

(all around me unfamiliar faces, foreign faces, Black Sea places – have that silly guy dancing)

He missed his wife. He missed his social life, and the great libraries of the city of Rome. Nobody spoke Latin. So naturally, he spent his time there in sad boy hours, writing depressing poetry. He died there, too, despite actually outliving the emperor by several years. Poor guy (Green, 15-51).

These guys weren’t the only ones to write about the Scythians, but they’re the most useful ones for our purposes. During our journey to uncover the history of the enarees, these three writers will be our ancient companions.

Scythian Women

Let’s start with Scythian women. This is a topic we just kind of glossed over in the original video, and I don’t think we did it enough justice.

Scythian women would serve as archers on horseback. Pseudo-Hippocrates tell us as young girls, they would have their right breast removed, in order to allow them to more easily fire a bow, quote:

“They have no right breast; for while still of a tender age their mothers heat strongly a copper instrument constructed for this very purpose, and apply it to the right breast, which is burnt up, and its development being arrested, all the strength and fullness are determined to the right shoulder and arm.”

(Hippoc. Aer. VI.XC).

Would this be helpful?

I don’t know. It doesn’t seem like it would be.

I’m not a master archerist or whatever but I did watch some YouTube tutorials. And they told me when you fire a bow, the arm that holds your bow should be straight out in front of you. Then you pull the string back with your other hand, and there you go.

But is that how they held it in the ancient world? It seems like it. Check this guy out, this is from a fragment of an attic black figure vase, held in the Met. It dates to around 550 BCE (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 2011.604.3.152). He’s holding a bow in the same way. And check out his cool white cap, that means he’s a Scythian. But this was made by Greeks, so there might be some creative licensing here. So here’s another one, from Kul’-Oba, a Scythian burial mound on the Cimmerian Bosporus, right near Pantikapaion (Cunliffe, 241) – the final capital of Hypsikrates and Mithradates’ empire. This was made by Scythians themselves, and they’re clearly holding the bow that way too.

And it seems like that wouldn’t really get in the way of firing a bow. I did talk to a couple of beboobled archers to get the real scoop on this, at the risk of looking like an absolute total weirdo. I’m grateful for the people who responded to my question about this on Bluesky, because sliding into a stranger’s DMs to ask them about their boobs is probably not going to go very well, and if you’re a skilled archer with big boobs who posts about it online you’re probably already getting a lot of comments about your boobs, and I don’t want to add to that. So thank you for the responses. From what I can gather, it doesn’t seem like big boobs would get in the way of firing a bow.

If it really did get in the way, I feel like it would be a whole lot easier to make a leather chest guard than to burn off one of your boobs. And we do know the Scythians made leather goods, including some made of human skin, yikes (Brant et al, abstract).

In fact, they were probably already doing this, since the Scythians were renowned horseback riders. And look, I don’t have big boobs, as you can see, but I’ve dated girls who do. And they’ve told me even running can be painful without the right support, so I can’t imagine how much worse that would be if you were galloping on a horse, even if you’ve only got one boob.

Talk to any trans guy who’s had top surgery, and he’ll tell you the recovery process isn’t easy, even with modern medicine and painkillers and antiseptics and better techniques than burning it off. And I’m not saying top surgery isn’t a necessary thing for those who need it, but what I am saying is if there were an easier way than surgery to get the job done, most trans guys would probably take it.

So the more I think about this one, the less I buy it.

Pseudo-Hippocrates also tells us about the behaviour of young Scythian women, quote:

“Their women mount on horseback, use the bow, and throw the javelin from their horses, and fight with their enemies as long as they are virgins; and they do not lay aside their virginity until they kill three of their enemies, nor have any connection with men until they perform the sacrifices according to law”

– Hippoc. Aer. VI.XVII

That’s a little more believable, and a little more badass, though perhaps still a little fantastical. But it’s quite a bit different than the role women played in Greek society, and the role women play in modern society as well.

But even if the Scythian women did have a breast removed in order to better fire a bow – and I do think that’s unlikely, to be clear – even if they did, that raises an important question. Is that transgender?

We might think of it that way today, since, illness aside, mastectomies are typically done for gender affirming reasons.

In the introductory chapter of this series, I talked about the problem of defining people as transgender in cultures where such a concept didn’t exist the way we think of it today.

Queer historian Susan Stryker’s definition of transgender in a historical sense is, quote:

“people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth, people who cross over the boundaries constructed by their culture to define and contain their gender.”

– Page 1

And if we go with this definition, the Scythian women were not transgender.

Basically, they were just the Scythian equivalent to cis girls, but the Scythians had different ideas around gender roles than we do.

Neato.

The Enarees

On the other breast, both writers talk about another group within Scythian society who give us quite a bit to explore.

Now this may come as a huge shock to you, but it turns out that sometimes people make up stuff.

I’m not talking about things that are obviously made up, like plays or novels. But sometimes, the ancients prove to us they’re about as reliable as a politician, or a corporate journalist when it comes to presenting actual unbiased truths.

But of course, a lot of information has been lost, so often we’re lucky if we even have a single source for things.

Sometimes, they’re pretty obviously rubbish – like the classic story of Caligula planning to make his horse consul – the next most important position in Roman government after the emperor. The closest source we have to Caligula who mentions this is Suetonius (Suet. Calig. LV), who wasn’t even born until almost 30 years after his death. When he tells us this, he mentions it off-hand like something he heard some guy say once – doesn’t inspire a whole lot of confidence.

It probably didn’t happen, and if it did, scholar Aloys Winterling suggests it wasn’t because Caligula was crazy, but more as a power move to show the Roman Senate that they were so meaningless under his reign that a horse could be consul and it wouldn’t change much (Winterling, 82). But that’s a whole other topic.

Cassius Dio mentions the Caligula thing as well (Roman History, LIX.XIV), remember him from the Elagabalus video? But he wasn’t even born until more than 30 years after Suetonius’ death. They likely based this story on hearsay.

So, okay, two sources saying the same thing, but there’s reasonable doubt. We’ve even looked at three people saying the same thing – again, the Elagabalus video. But if two people say the same thing, and one isn’t clearly parroting the other, and they’re both not clearly influenced by a third source that’s now lost, it tends to have a little more credibility.

We don’t often get this.

But with the enarees, we do.

At least, sort of. Herodotus refers to them as enarees, while Pseudo-Hippocrates calls them Αναριεις (Anareies) (106).

But they’re certainly referring to the same thing (Penrose, 38). It’s possible this was a transliteration of a Scythian word, and these two writers interpreted it differently. I’m going to refer to them as enarees though, for simplicity’s sake.

Pseudo-Hippocrates begins:

“And, in addition to these, there are many eunuchs among the Scythians, who perform female work, and speak like women. Such persons are called enarees. The inhabitants of the country attribute the cause of their impotence to a god, and venerate and worship such persons, every one dreading that the like might befall himself… They put on female attire, reproach themselves for effeminacy, play the part of women, and perform the same work as women do.”

– Hippoc. Aer. VI.CVI.XXII

When he talks about the enarees “playing the part of women,” it’s not clear what specifically he means here.

He may be saying they play what he would assume to be a womanly role, based on his own cultural biases, or that they were horseback warriors. Based on the way he describes them, though, it seems like the former.

I’m also not sure whether he’s referring to them “playing the part of women” in a sexual way, which to the Greek mind would have meant playing a receptive role. There may be some context in the original Greek that can reveal that, but I only know Latin, so I’m not able to glean that. If someone watching this does understand Greek, I’d love to hear your take on it – drop it in the comments below.

Herodotus, on the other hand, tells us more about the spiritual role of the enarees.

“There are among the Scythians many diviners, who divine by means of many willow wands as I will show. They bring great bundles of wands, which they lay on the ground and unfasten, and utter their divinations laying one rod on another; and while they yet speak they gather up the rods once more and lay them one by one; this manner of divination is hereditary among them. The enarees, who are androgynous, say that Aphrodite gave them the art of divination, which they practice by means of lime-tree bark. They cut this bark into three portions, and prophesy while they plait and unplait these in their fingers.”

– Hdt. IV.LXVII

In the Pseudo-Hippocrates quote, he mentions the enarees blamed a god for their being the way they are. Herodotus expands on that.

“When the Scythians came on their way to the city of Ascalon in Syria, most of them passed by and did no harm, but a few remained behind and plundered the temple of Heavenly Aphrodite… and all their descendants after them, were afflicted by the goddess with the female sickness, and so the Scythians say that they are afflicted as a consequence of this.”

– Hdt. I.CV

And, oh wow. There’s so much packed into these short paragraphs.

The enarees were what we might consider today to be assigned male at birth, clearly. Yet they dressed like women, spoke like women, played a woman’s role in Scythian society, and also had a special, spiritual role in Scythian life.

Take a moment to consider all that. I mean really, think about it. This is evidence of a transgender population that existed within a society from two and a half millennia ago.

That’s the oldest thing we’ve looked at on this channel so far – but by no means the oldest thing I’ve encountered. More on that in a future video.

Incredible stuff. Trans people predate almost everything!

But as you can see if you look at the status bar at the bottom of this video, there’s lots more to cover. The truth is that revealing a smoking gun for evidence of ancient trans people is not the most exciting part of my research here. Stay with me, it gets cooler.

Herodotus seems to talk about the enarees mostly in relation to a group of Scythians he calls the Royals, who lived east of the Gerrus river (today it’s the Molochna river, in southern Ukraine). The Scythian king and his family did live near here, but not all the Royal Scythians were part of the royal family, if that makes sense.

One of the ways the enarees served as diviners was when the king was ill. He would call upon the three most respected enarees in the community to use their powers of divining to figure out who was cursing him (Her. IV.LXXVIII). This is the only specific situation either writer mentions where they use their divining skills, but since the king, presumably, didn’t get sick every day, they must have had more to do as well.

In general, it seems like a pretty important job.

So it’s a little weird that Pseudo-Hippocrates says they were ashamed of their effeminacy. Whether he actually observed them displaying shame, or his own cultural biases were creeping in, or he just really wasn’t into trans girls, it’s hard to say.

When Herodotus describes the enarees, he says they have a “female sickness” (Her. I.CV). Pseudo-Hippocrates says the members of Scythian elite society, having worn tight trousers and rode on horseback all the time, were impotent. There is actually limited modern research that supports this idea as well (Turgut Et. Al, as cited in Williams). As a result, many scholars tend to just assume Herodotus was talking about their impotence and move on with their lives to study much more important, dignified topics, like whether or not Sappho was into ladies.

But Rachel Hart points out in her paper, the name of which isn’t really readable so I’m just going to stick it on the screen here, – (N)either Men (N)or Women – see what I mean? How would you read that?

Anyway, she says that Herodotus describes other nad-related illnesses elsewhere in his work but he doesn’t use the same terms as he does here (Hart, 6). So what exactly was he talking about when he referred to the “female sickness”?

We might have an answer in Ovid’s Amores. In Book 1, elegy 8, he says, quote:

“There’s a certain old woman called Dipsas… She knows what herbs to use, how to whirl the bullroarer, and the value of the virus from a mare in heat.”

– Ov. Am. I.VIII

So, what?

At face value that might not seem like much, so let’s dig a little deeper.

First, let’s understand what the word virus means. It’s a Latin word that I left untranslated. Yes, it might look like the word virus, but it’s not. It means a poison, a strong smell, animal seed, active ingredient, that sort of thing.

Here’s where we run into a problem.

In the original video, I mentioned Ovid wrote his Amores while living in exile among the Scythians, but that’s not true.

He wrote it while still living in Rome, and I made a mistake, which of course means that everything I’ve ever said should be thrown out and trans history isn’t real it’s all just some junk made up by THE WOKE MOB to destroy western civilization or whatever.

No, it doesn’t – for the most part, my research is solid. If you take a look in the bio below, you’ll find a link to the script of this video, with a full bibliography and in-line citations. I’ve learned my lesson. I can back up any claim I’ve made in this video.

Be nice to me, we all make mistakes sometimes!

So, it no longer works to assume Dipsas was a Scythian woman, unfortunately. However, when Ovid took his gap year, he tells us he traveled across Sicily, Greece, and Asia Minor (Green, 25). Shortly after returning, he completed and released his Amores. How close did he get to the Scythians while he traveled?

In his Fasti, which he actually did finish while in exile – I’m sure of it this time (Boyle & Woodard, xxxv) – he tells us he visited Dardania, which is close to the city of Troy (Ov. Fast. VI-CDXX-CDXXV).

In his Epistulae Ex Ponto – Black Sea Letters, which he also wrote in exile – do I need to cite this one? Look at the name of it. Clearly he didn’t write it in Rome – he says he’d “gazed at splendid cities of Asia” (Pont. II.X) but he doesn’t say which ones specifically.

Could he have been to Scythian territory during his travels? It’s possible, but considering that Ovid points out how much different life is in Tomis compared to the places they visited (Pont. II.X), I think it’s unlikely.

So who’s Dipsas?

She’s a Lena.

A type of stock character who commonly shows up in Roman elegy. She’s a crafty old hag who brews potions and creates magic spells, which she sells to a lovesick poet or to his rival (Dickson, 176).

But even if Dipsas isn’t based on a Scythian hag, it’s still interesting to explore the virus of a mare in heat.

Because believe it or not, modern science has shown us that the urine of a pregnant mare is actually one of the most potent natural sources of estrogen available. In fact, the drug Premarin, which is one of the most common estrogen supplements, is literally a contraction of the words PREgnant MAre uRINe (Vance, abstract).

This wasn’t the only time Ovid talks about it either – in another poem, Cosmetics For The Female Face, he mentions the extract of a pregnant mare as a beauty treatment for women.

“Don’t touch any witch’s hand-picked urticant roots, steer clear of her horrid craft. Put no faith in herbals and potions, abjure the virus distilled by a mare in heat.”

– Ov. Medic. XXXV-XXXVIII

I don’t want to recite the entire poem here, but after the line I just quoted, he talks how being kind and polite are the best ways to stay beautiful, which, yeah, no kidding. Have you seen right wing women? Hate makes you ugly. Then he actually gets into some treatments, and a couple of them are still being used today – like using oatmeal and egg whites.

Admittedly, he suggests that women not use the virus, but the fact that he mentions it so casually means he assumes the reader would have heard of it before. Otherwise, why would he teach someone about something he didn’t want them to do when he could just not mention it?

So it’s reasonable to assume this sort of treatment was fairly widely known.

Now, I’m sure horse piss would smell horrible.

Wait.

Video of me googling “what does horse piss smell like?”

Okay, so horse piss smells awful. So maybe he was suggesting other treatments that might work better without taking a bath in…oh lord we’re moving on now.

We do know today though that applying estrogen to one’s face can have an anti-aging effect. In fact, applying Premarin to the faces of postmenopausal cis women thickens their skin and reduces wrinkles (Woods and Warner). So this treatment would have worked, if you knew how to extract the virus of course.

Where did the Romans get this idea from? It’s difficult to say. Ovid wrote both of these poems while still living in Rome, and it’s unlikely he had any connection with the Scythians at the time. But it’s not impossible to imagine the Scythians would have known about this as well, or at least that they would have come upon something similar.

Would It Actually Work?

So yeah, pregnant mare urine has enough estrogen in it that we can make Premarin from it. But there’s obviously a process involved there. Would it work to just… drink a glass of horse pee to feminize yourself?

Believe it or not, there’s been research on this.

Scholar Andrew N. Williams did the math on it. Pregnant mare urine has about 0.1mcg of estrogen per millilitre. Meanwhile, the minimum therapeutic dose for trans women according to current WPATH guidelines is 2.5mg daily (WPATH 254). To get even that minimum level, you’d have to drink 25 litres per day, and yeah, not gonna happen.

So, no, it doesn’t seem possible to feminize yourself by drinking pregnant horse urine. I know that’s devastating news for a lot of you, I’m really sorry.

HOWEVER, there is hope!

Williams then considers a study showing how cheese curds absorb a lot of salt from the brine they float in. From there, he extrapolates how those same curds could be used to absorb estrogen as well.

Make this part a cooking video, of me doing stuff in the kitchen while I narrate this next part

If you take some cheese, put it in some cheese cloth, put some pregnant mare’s horse piss in a bowl, soak the cheese in the piss, toss out the piss, get some more piss, soak it again, and do this several more times, you’ll get a tasty treat that gives you all the estrogen you’ll need.

So, there you have it. Out with the drinking horse pee meme, in with the eating estrogen cheese meme.

(say the next part as I eat cheese curds soaking in a clear cup with beer in it)

Is there any evidence the enarees actually did this? No. But I’m also not sure what type of evidence there could be for it. But the Scythians did make cheese (Cunliffe, 222-4), they did have clay pots (Rolle, 88, 119), and they did have horses which, presumably, were sometimes pregnant.

So it’s conceivable.

What May Have Been

If the Scythians were able to distill the virus of a pregnant mare’s urine, and they knew what effect it had, did the enarees use it on themselves?

If the enarees were eunuchs, they wouldn’t have needed anti-androgens. And if they weren’t eunuchs, they might have been able to get away with estrogen monotherapy combined with the licorice root they frequently ate (Sabbadin). After all, licorice does have anti-androgen properties (Grant & Ramasamy).

And of course, equine estrogens can be used as feminizing hormone therapy, and have been in the past, though it’s less common today.

So could the “female sickness” Herodotus talks about just be… ancient Scythian horse piss hormone replacement therapy?

The answer is… maybe. It’s a stretch, admittedly, but not a huge one.

And hey, if you want to imagine a culture of glamorous ancient Scythian trans women who eat estrogen soaked cheese curds with their wine and are revered by the men in their society, go ahead. It’s not illegal, the cops can’t stop you.

Besides, white dude chuds like to imagine a history where brave Spartan warriors were totally heterosexual and definitely not banging each other so I think we’re allowed a little self-indulgent historical musing as well.

How likely was it that the enarees actually used ancient Scythian horse piss HRT? Herodotus and Pseudo-Hippocrates spill a fair amount of ink telling us how effeminate they are, how they serve womanly roles in their society, how much they resemble women, etc. But there are at least a couple of smoking guns that would make it pretty obvious if they’d had some sort of hormone treatment.

A couple of telltale signs that estrogen had done its duty. But our ancient companions don’t bring that up, one way or another.

So, unfortunately we can’t confirm whether ancient Scythian horse piss HRT was a real thing, even though it’s theoretically possible to create.

But that aside, it’s clear that the enarees transed the boundaries of gender within Scythian society, and seemed to be not only accepted, they played an important role in it.

Herodotus and Pseudo-Hippocrates both wrote their works during the 5th century BCE. Most scholars agree the New Testament of the Bible was written during the 1st century CE. What this means is that we have reliable, documented evidence of a transgender population existing at least 400 years before Christianity.

Before Christ hung in agony on the cross, we were here.

Before anybody named Caesar, Octavian, Cicero, or Mark Antony walked the Earth, we were here.

Before Rome was anything more than a forgettable backwater town, we were here.

Before Alexander ran roughshod across Persia, we were here.

Before Athens and Sparta crossed spears with one another, we were here.

We have always existed. And so long as humanity continues to endure, so too shall we.

Ancient Sources:

►Aristotle. “Nicomachean Ethics”. Translated by W.D. Ross. Oxford University Press, 1980.

►Cassius Dio. “Roman History”. Translated by Earnest Cary. Harvard University Press, 1927.

►Herodotus. “Histories”. Translated by C. Hude. Oxford University Press, 1927

►Herodotus. “Histories”. Translated by George Rawlinson. Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions, 1996

►Ovid. “Amores”. Translated by A.S. Kline, 2003

►Ovid. “Epistulae Ex Ponto”. Translated by A. S. Kline, 2003

►Ovid. “Fasti”. Translated by A.J. Boyle and R.D. Woodard, Penguin Books, London, 2000

►Ovid. “Medicamina Faciei Femineae”. Translated by Peter Green, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1982

►Ovid. “Tristia”. Translated by A. S. Kline, 2003

►Pseudo-Hippocrates. “On Airs, Waters, and Places”. Translated by Francis Adams

►Strabo. “Geographia”. Translated by Horace Leonard Jones, Loeb Classical Library, 1928

►Suetonius. “The Life Of Caligula”. Translated by Maximilian Ihm, Loeb Classical Library, 1913

Modern Sources:

►Bar, Doron. “Rural Monasticism as a Key Element in the Christianization of Byzantine Palestine”. The Harvard Theological Review. 98, 2005, 49–65.

►Cunliffe, Barry. “The Scythians.” Oxford University Press, 2019

►Curry, Andrew. “RITES OF THE SCYTHIANS.” Archaeology, vol. 69, no. 4, 2016, pp. 26–32.

►Danby, Herbert. “The Mishnah: Translated from the Hebrew with Introduction and Brief Explanatory Notes.” Hendrickson Publishers, 2012.

►Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. “Enarees and Women of High Status Evidence of Ritual at Tillya Tepe (Northern Afghanistan)” Kurgans, Ritual Sites, and Settlements: Eurasian Bronze and Iron Age, 2000, pp. 223-239.

►Grant, Paul, and Ramasamy, Shamin. “An update on plant derived anti-androgens.” International journal of endocrinology and metabolism vol. 10,2 (2012): 497-502. doi:10.5812/ijem.3644

►Morris, Ian, and Walter Scheidel. “The Dynamics of Ancient Empires: State Power from Assyria to Byzantium.” Oxford University Press, 2009

►Murphy, Eileen M. “Herodotus And The Amazons Meet The Cyclops: Philology, osteology, and the Eurasian Iron Age.” Archaeology and Ancient History: Breaking down the Boundaries, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Taylor & Francis Group, 2004

►North, Michael. “Ancient Greek Medicine”, National Library of Medicine, 2008.

►Peterson, Sara. “Roses, poppies and narcissi : plant iconography at Tillya-tepe and connected cultures across the ancient world.” PhD thesis. SOAS University of London, 2016.

►Pollio, Antonino. “The Name of Cannabis: A Short Guide for Nonbotanists.” Cannabis and cannabinoid research vol. 1,1, 2016, 234-238.

►Rainey, Anson F. “Herodotus’ Description of the East Mediterranean Coast.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 321, 2001, pp. 57–63.

►Rolle, Renate. “The World of the Scythians”. Translated by F.G. Walls, University of California Press, 1980

►Simpson, St. John. “Scythians, ice mummies, and burial mounds.” British Museum Blog, 2017

►Stryker, Susan. “Transgender History.” Berkeley, CA, Seal Press, 2008

►Truemper, Monica. “Baths & Bathing, Greek.” Greek Baths And Bathing Culture: New Discoveries And Approaches, pp. 784-798, 2013

►Turgut, A.T., Kosar, U., Kosar, P., Karabulut, A. “Scrotal sonographic findings in equestrians.” Journal of Ultrasound Medicine 24: 7: 911-7, 2005

►Vance, Dwight A Dph. “Premarin: the intriguing history of a controverisal drug.” International journal of pharmaceutical compounding vol. 11,4: 282-6, 2007.

►Villing, Alexandra. “Historical City Travel Guide: Athens, 5th Century BC.” British Museum Blog, 2020.

►Williams, Andrew N. “Did Scythian Men Feminize Themselves By Drinking Mare’s Urine?” University of Leicester, 2023.

►Winterling, Aloys. “Caligula: A Biography,” translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider, Glenn W. Most, and Paul Psoinos, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011.

►World Bank Group. “Climate Change Knowledge Portal: Mongolia.” 2021.

►World Wildlife Fund. “Thirsty Crops”

►Woods, James, and Elizabeth Warner. “Does Estrogen Help Age Skin Better?” University of Rochester Medical Center, 2015.

►WPATH. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health, 2022.

►Yano, Hiroyuki, and Wei Fu. “Hemp: A Sustainable Plant with High Industrial Value in Food Processing.” Foods (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 12,3 651. 2 Feb. 2023